Surgical Treatment of Canine T-Cell Lymphoma in a Dog

Now that I’ve covered the clinical signs and diagnosis of Cardiff’s illnesses (most strongly suspected to again be cancer), it’s time to move on to the treatment phase. This week, the topic is surgery.

Cardiff has previously been through abdominal exploratory surgery to remove a loop of small intestine having a mass-like lesion which biopsied as T-cell lymphoma in December 2013, so I’m familiar with the surgical process and his anticipated recovery. I even assisted during Cardiff’s prior surgery, so I had the firsthand experience of seeing and feeling the tumor inside his abdomen.

This time things are a little bit more complicated because we are dealing with the likelihood that his cancer has recurred, so I sought consultation with a board certified veterinary surgeon.

ACCESS LA’s Justin Greco DVM, DACVS shared his perspective on the available treatment options (chemotherapy or surgery) and we've concluded that surgery followed up by chemotherapy would be the best route for Cardiff.

Why Surgery for Cardiff’s Lymphoma?

As a mass-like lesion on Cardiff’s small intestinal suspected to be a tumor is the cause of his current health issues, surgery may even be somewhat curative. After all, a chance to cut is a chance to cure.

Lymphoma can manifest anywhere in the body where there are white blood cells, so common sites include the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, gastrointestinal tract, eye, and nervous system (brain, spinal cord, etc.). Yet, it’s uncommon for Lymphoma to appear as a single tumor, like it is seemingly again doing in Cardiff’s case, instead of diffusely affecting an entire organ system or the whole body.

Because Cardiff’s mass-like lesion is causing a partial obstruction of his small intestine and causing his clinical signs of lethargy, decreased appetite, vomiting, and stool abnormalities, surgery really is the most ideal treatment. Surgically removing the lesion will alleviate the obstruction, best allow for a biopsy to be attained, and permit an official diagnosis to be determined. Additionally, surgery has the potential to immediately put Cardiff into remission if no other tumors nor evidence that the cancer has spread from its original site (metastasis) is found.

How Was This Surgery Different From the One Cardiff Underwent in 2013?

Dr. Greco found the tumor on Cardiff’s duodenum, which is the section of the small intestine that connects the stomach to the jejunum (the second of three sections of small intestine). This is a different site from where his cancer was discovered in 2013, which was the jejunum (section of small intestine between the duodenum and the ileum).

The proximity of the current mass to the ducts through which the pancreas secretes digestive enzymes into the small intestine created some concern, but there was enough distance between the mass and the pancreatic ducts for Dr. Greco to fully remove the mass and leave the ducts undamaged.

Dr. Greco removed the new intestinal mass along with sufficient normal tissue higher up and lower down the duodenum to ensure the mass was completely excised. Additionally, he removed the healed site of Cardiff’s prior intestinal surgery, as it was adjacent to the current mass and exhibited some scarring that can reduce the flow of liquid and food through his intestines. This procedure, where an unhealthy section of intestine is removed and then the healthy pieces are sutured together, is called a resection and anastomosis (“R and A”).

Cardiff’s intestinal mass is the redder, thicker area of tissue on the right, closest to the clamp that it attached to the small intestine.

Cardiff also had a cystotomy (surgical opening of the bladder) to remove four small (1-2 mm diameter) stones while he was under for the abdominal exploratory procedure. Although he was not clinical for any urinary tract signs commonly seen with bladder stones (straining to urinate, abnormal urinary patterns, bloody urine, etc.), it was best to remove the stones before they got larger or caused a urinary obstruction.

Was Cardiff’s Surgery a Success?

Yes, the surgery was a success. The mass-like lesion was easily localized and removed. No other evidence of cancer could be discovered on visual examination nor palpation (touching with one’s hands) of Cardiff’s internal organs.

The surgical refresh of his intestines was a brilliant idea on behalf of Dr. Greco, as only leaving one location where there could be reduced capacity to contract and relax resulting from scar tissue will promote a more normally-functioning digestive tract.

Biopsy samples of the liver and lymph node adjacent to the mass were collected to determine if there’s been any detectable spread of tumor cells.

The original plan was to also remove nine superficial (on the surface) skin masses on multiple body surfaces in addition to the abdominal procedure. Unfortunately, the need to perform a cystotomy required Cardiff to be under anesthesia for longer and his blood pressures weren’t staying within the normal range without the intervention of pressure-promoting drugs.

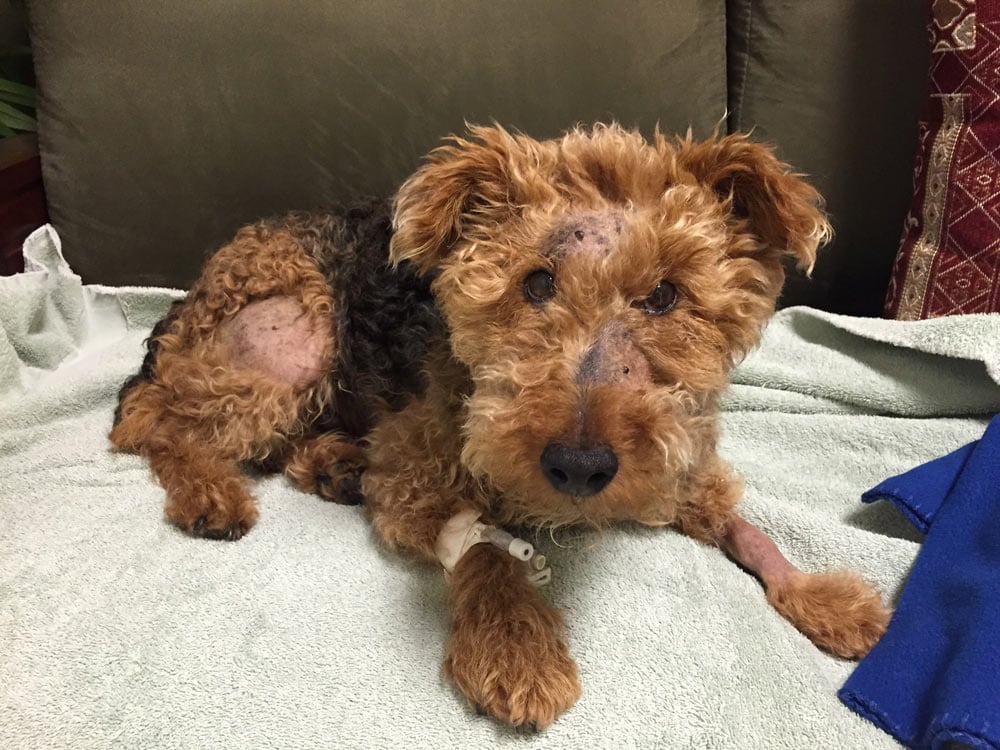

So, Cardiff woke up after the procedures looking like a patch-work dog with large areas of shortly-clipped hair around his skin masses. I’ll take a patch-work dog who made it through his crucial surgeries and had a normal recovery any day over a canine companion having a likely-cancerous intestinal mass compromising his quality of life lingering inside his body.

Cardiff the patch-work dog (shaved sites around skin masses yet to be removed) recovering from his abdominal surgery.

Stay tuned for Cardiff’s biopsy findings.

Dr. Patrick Mahaney

Image: Cardiff enjoying a sunny California day

Related Articles

When Cancer That Was Successfully Treated Reoccurs in a Dog

What Are the Signs of Cancer Reoccurence in a Dog, and How is it Confirmed?