Feline Heart Disease and Nutrition, Part 1

It is widely believed by both veterinarians and pet owners that heart disease is uncommon in cats. Actually, studies suggest that the incidence of murmurs and heart disease may be as high as 15-21 percent in the cat population. One study that followed cats with murmurs that had subsequent echocardiographs confirmed that 86 percent of those patients had cardiac disease that primarily involved the heart muscle. Although some feline heart disease is closely associated with nutrition deficiencies, nutritional intervention strategies are limited in preventing feline heart disease.

Types of Feline Heart Disease

Unlike dogs, heart disease in cats primarily affects the heart muscle rather than the heart valves. There are presently two major categories of feline cardiac disorders, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM).

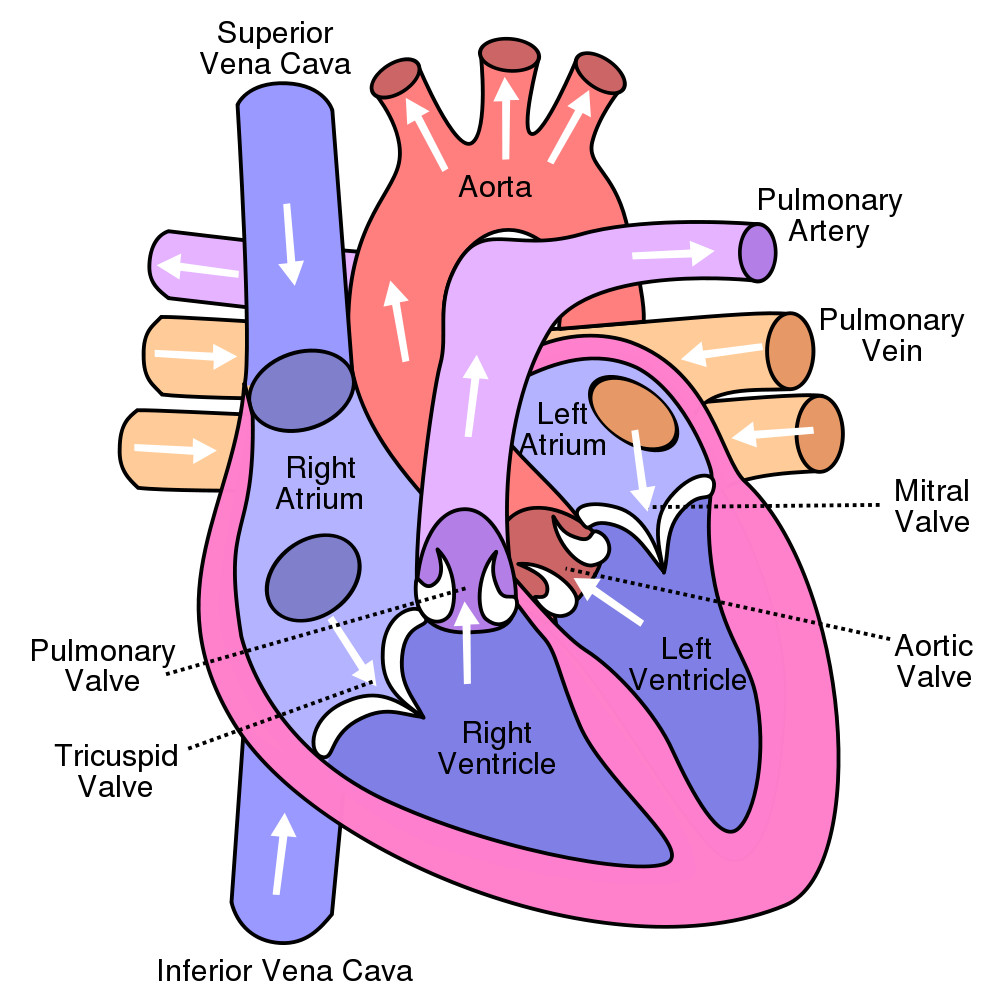

The heart muscle is divided into halves separated by a muscular wall. Each half is divided by the tricuspid valve on the right side and the mitral valve on the left to form the four chambers.

Blood passively flows into the upper chambers, or atria, and through the valves to the ventricles. The muscular contraction (the heart beat) increases pressure in the ventricles, closing the tricuspid and mitral valves, and pumps the blood into the pulmonary and aortic arteries. Pulmonary arterial blood is destined for the lungs to replace its oxygen supply while fully oxygenated blood is pumped to the rest of the body through the aorta. The increased flow of blood through these vessels during contraction closes the pulmonary and aortic valves to prevent any back flow into the ventricles between beats.

All heart chambers are enlarged or dilated in cats with DCM. The muscle is often thin and has reduced contractile strength, which limits blood flow from the heart. Chamber enlargement affects valvular function, so murmurs are a common early symptom of DCM. Inadequate blood flow from weak heart contractions causes increased pooling of blood in the veins of the heart liver and other organs. This venous accumulation of blood increases pressure on the vessel walls and forces fluid into the chest and abdominal cavity. Most cats with DCM eventually develop congestive heart failure (CHF). Initial symptoms of CHF may include decreased activity, decreased appetite, coughing or breathing abnormalities, exercise intolerance, and abdominal enlargement or distension. Without treatment, symptoms progress to rapid shallow breathing and panting, respiratory distress, grey or blue gums, and severely distended abdomen.

DCM was the most common type of feline cardiac disease until a 1987 study documented the association of DCM with taurine (an amino acid-like molecule) deficiency, and the reversal of the condition with taurine supplementation. Increased taurine levels in commercial cat food since that study have decreased the incidence of DCM. But there is still one population of cats at high risk for developing the condition (more in Part 2).

With HCM, the left ventricular muscle becomes enlarged, or hypertrophic. This genetic condition promotes muscular growth that decreases the size of the left ventricle and limits passive filling between beats. HCM also leads to CHF, so symptoms are much the same as those for DCM. Additional symptoms include heart arrhythmias, fainting, and sudden death. This condition also promotes blood clot formations that lodge in the legs and other areas. The most common site for clots is where the aorta forks to form the arteries to the hind limbs. Cats with this “saddle thrombus” suddenly become weak or paralyzed in the hind limbs. Due to the lack of blood flow, these limbs feel cool or cold to the touch.

The prognosis for both DCM and HCM are poor, especially after they progress to CHF. With the exception of taurine, nutritional modification and supplementation has not shown much promise in feline heart disease. We will investigate further in Part 2.

Dr. Ken Tudor

Image: wabang70 / via Shutterstock