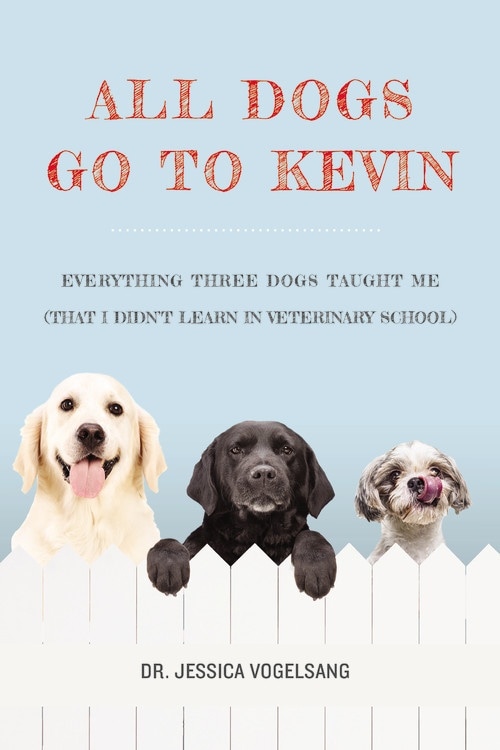

Read Excerpts from Dr. Jessica Vogelsang's Memoir, 'All Dog's Go To Kevin'

This week we're reading Dr. Vogelsang's new memoir, All Dogs Go To Kevin, and thought you might enjoy reading some of it, too. It is scheduled for release on July 14th, but is available for pre-order now. You can find out more about where you can order here at the publisher's site.

In the meantime, join us in reading some excerpts from her memoir, and please help us to congratulate Dr. V on her first book by leaving a comment.

-------

Chapter 17

I have long held the opinion that crummy medicine is most often a by-product of crummy communication. While some veterinarians may simply be poor at the task of diagnosing disease, the vast majority of veterinarians I’ve known are excellent clinicians, regardless of their personality. More often than not we are failing not in our medicine but in relaying to our clients, in clear and concise terms, the benefit of what it is we are recommending. Or even what we are recommending, period. Muffy was a patient I hadn’t seen before, a one-year-old Shih Tzu who presented to the clinic for sneezing spasms. They had started suddenly, according to the client, Mrs. Townsend.

“So he doesn’t have a history of these episodes?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” she replied. “I’m just dog-sitting for my daughter.”

As we spoke, Muffy began sneezing again— achoo achoo aCHOO! Seven times in a row. She paused, shaking her fuzzy little white head, and pawed at her snout.

“Was she outside before this happened?” I asked.

“Yes,” Mrs. Townsend said. “She was out with me for a couple of hours this morning while I was weeding the garden.”

Immediately my mind jumped to foxtails, a particularly pervasive type of grass awn found in our region. During the summer months, they have a nasty habit of embedding themselves in all sorts of locations on a dog: ears, feet, eyelids, gums, and yes, up the nose. Working like a one-way spearhead, these barbed plant materials are known for puncturing skin and wreaking havoc inside the body. It’s best to get them out as quickly as possible.

Unfortunately, due to the nature of the little barbs on the seed, foxtails don’t fall out on their own—you have to remove them. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you can pull one out of the ear canal while a pet is awake, but noses are a different story.

Unsurprisingly, the average dog has no interest in holding still while you slide a well-lubricated pair of alligator forceps up his or her nose to go fishing for foxtails in their sensitive sinuses. And it’s dangerous—if they jerk at the wrong moment, you are holding a piece of sharp metal one layer of bone away from their brain. The standard nose treasure hunt in our clinic involved general anesthesia, an otoscope cone functioning as a speculum to hold the nares open, and a smidgen of prayer.

I explained all of this as best I could to Mrs. Townsend, who eyed me distrustfully from behind her cat-eye glasses, blinking as I told her about the anesthesia.

“Can’t you just try without the anesthesia?” she asked.

“Unfortunately, no,” I said. “It would be impossible to get this long piece of metal up her nose safely without it. Her nostrils are very small and it would be very uncomfortable for her, so she wouldn’t hold still.”

“I need to talk to my daughter before we do that,” she said.

“I understand. Before we anesthetize her, we do need your daughter’s consent.”

Muffy left with Mrs. Townsend and a copy of the estimate. I was hoping to have them back in that afternoon so we could help the dog as quickly as possible, but they didn’t return.

The next day, Mary-Kate scurried into the back and came trotting toward me, loud voices pouring into the treatment area as the door swung shut behind her.

“Muffy’s owner is here,” she said. “And she’s MAAAAAD.”

I sighed. “Put her in Room 2.”

Like a game of telephone, trying to communicate what’s going on with a dog who can’t talk to owners who weren’t there via a pet-sitter who misheard you is bound to cause one or two misunderstandings. When Mrs. Townsend relayed her interpretation of my diagnosis to her daughter, the daughter rushed home from work and took Muffy to her regular veterinarian, who promptly anesthetized the dog and removed the foxtail.

“My vet said you are terrible,” said Muffy’s owner without preamble. “Didn’t you know foxtails can go into the brain? You nearly killed her!” Her voice reached a crescendo.

“I think there might be a misunderstanding here. I wanted to remove it,” I told her.

“The pet-sitter—it was your mother, correct? She said she needed to talk to you before approving the estimate.”

“That’s not what she said,” replied the owner. “She said that you said there was no way a foxtail would fit up there and we should put her to sleep. Well there was one up there! You were wrong and you almost put her to sleep because of it!”

I took a slow inhale and reminded myself not to sigh. “What I told your mother,” I said, “was that I thought Muffy had a foxtail, but there was no way I was going to be able to remove it without anesthesia. So I gave her an estimate for all of that.”

“Are you calling my mother a liar?” she demanded. This was not going well.

“No,” I said, “I just think that she may have misheard me.”

“OK, so now you’re saying she’s stupid.” I silently prayed for a fire alarm to go off, or an earthquake to rumble though. The waves of indignant anger pulsing from this woman were pressing me farther and farther into the corner and there was no escape.

“No, absolutely not,” I said. “I think maybe I just didn’t explain myself well enough.” I pulled the record up on the computer and showed her. “See? She declined the anesthesia.”

She thought about it for a minute and decided she still wanted to be mad. “You suck and I want a refund for the visit.” We provided it gladly.

Recommended Pet Products

Chapter 20

He was right. Kekoa was shaped more like a cartoonist’s exaggerated rendition of a goofy Lab than an actual Labrador.

Her head was disproportionately small, and her wide barrel chest was supported by four spindly legs. The total effect was that of an overinflated balloon. But we didn’t choose her for her aesthetics.

When she would lumber over and plop on my feet, her skinny tail smacking into the wall with such force you’d think someone was cracking a whip on the drywall, she never seemed to notice. Such was her excitement that she paced from foot to foot as she stood near me, massive, looming, and then with the gentlest motion eased her tiny head into my hands and covered them with kisses. I tried to push her head away when I’d had enough, but then she kissed that hand too, so eventually I just gave up. Her tail never stopped wagging the entire time. I’d fallen in love.

Whenever the kids stretched out on the floor, Kekoa scurried over, thump-thump-thump, and hovered over them like the Blob. She melted onto them, all tongue and fur, dissolving into a puddle of their delighted giggles. After wedging herself in between Zach and Zoe, scooting her hips back and forth to make room, she’d contentedly roll onto her back, kick her legs up in the air, and occasionally let out a small fart.

We left the windows open and tolerated the occasional poor photograph, because, well, no one ever said My dog’s photogenic qualities make me feel so cozy and loved.

We bought one of those really expensive vacuums, because fur tumbleweeds skittering across the floor is a small price to pay for the comforting pressure of a happy dog leaning into you for butt scratches. And we kept plenty of paper towels and hand sanitizer around because as gross as a string of sticky saliva is on your forearm, it was utterly charming to be so loved that Kekoa could quite literally just eat you up.

This complete and probably undeserved adoration of human companionship came with a heavy price tag, however. Kekoa would very much have loved to have been one of those four-pound pocket dogs one could carry effortlessly into the mall, the post office, and work, a permanent barnacle on those she loved best. Sadly, as a seventy-pound sphere of gas, fur, and saliva, there were many occasions when she had to remain at home by herself, and each and every time we left she mourned deeply, as if we were heading off for a long deployment and not a two-minute trip to the 7‑Eleven.

When she was stuck with no one but the cat to keep her company, she funneled her pain, anxiety, and deep, pervasive grief into “music.” She sang a song of misery, a piercing wail of heartbreaking angst that shattered glass and the sanity of those near enough to hear it on a regular basis. The first time I heard her howling, I paused in the driveway and looked out the window to see which direction the approaching ambulance was coming from. The second time, I thought a pack of coyotes had broken into the house. The third time, only day seven of her life with us, Brian and I stepped out to say hello to a neighbor and heard her ballad of woe through our open front window. BaWOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO! OOO!

ArrrrrroooooOOOOOOoooooooo! So this was why she had lost her last home.

“Is she sad?” asked the neighbor.

“I think she misses us,” I said, then, gingerly, “Can you hear this from inside your house?” Thankfully, they shook their heads no.

“Well, at least she doesn’t do it while we’re home,” I said to Brian as he grimaced in the direction of the house. “And she’s not destructive!”

The next day, I came home after taking the kids to school and pulled into the driveway, listening intently for the song of the sad. It was blessedly quiet. I opened the front door, and Kekoa came skittering around the corner excitedly, knocking the cat aside in her exhilaration.

“Hi, Kekoa,” I said, reaching down to pat her. “Did you miss me the fifteen minutes I was gone?”

When I removed my hand from her head, I noticed my fingers were coated in a sticky substance. I looked down at her, innocently wagging her tail with a sheen of white powder stuck to her nose, the edges of her lips, and, when I looked down, her paws. Wondering why my dog suddenly looked like Al Pacino after a coke binge in Scarface, I went around the corner and saw the pantry door ajar. A mostly empty cardboard box of powdered sugar, chewed to a barely recognizable state, lay forlornly on the kitchen floor, massacred in an exsanguination of white powder. I looked at Kekoa. She looked back.

“Kekoa,” I said. She wagged her tail.

“KeKOA,” I said again, sternly. She plopped down on the pile of powdered sugar and continued to wag at me, licking the sticky sugar paste on her nose. It took me the better part of two hours, mopping and grumbling, to get that mess cleaned up.

The next day, I made sure I pulled the pantry door shut before taking the kids to school. This time when I returned, the house was quiet yet again. Maybe she just needed some time to adjust, I thought, opening the door. No Kekoa. See how calm she is? We’re getting there, thank God.

“Kekoa!” I called again. Nothing. The cat wandered around the corner, gave me an indifferent flick of the tail, and glided back over to the windowsill.

Perplexed, I walked around the bottom floor, winding up again in the kitchen. There was the pantry door, still shut.

“Kekoa?” I called. “Where are you?”

Then I heard it, the quiet thump-thump-thump of a tail whacking a door. The sound was coming from inside the pantry. I pulled the door open and out she tumbled, a pile of wrappers, boxes, and crackers falling out behind her in a landslide across the freshly mopped floor. She immediately ran over to the other side of the kitchen island and peeked back at me, her tail nervously swishing from side to side, Goldfish crumbs spraying with each shake.

I was so confused I couldn’t even get upset. How the heck did she do that? She must have pushed the handle down with her nose, wedged herself into the pantry, and accidentally knocked the door shut behind her with her rear end. In her combination of fear and elation, she had devoured almost every edible item on the bottom three shelves. Fortunately most of the items were canned foods, but there was still plenty of carnage. Half a loaf of bread. A bag of peanuts. Pretzels.

I scanned the bags, from which she had expertly extracted the edible bits, for signs of toxic food items and to my relief found no chocolate wrappers or sugar-free gum, two things that might have added “emergency run to the clinic” to my already packed to‑do list.

Peering back in, I noticed a bunch of bananas nestled among the cans of beans and soup, the sole survivor of the slaughter. Apparently, peeling them was too much work. Surveying the disaster before me, I tried to figure out what I was going to do. That afternoon, my son looked at me thoughtfully and asked, “Why doesn’t Koa go to preschool if she gets so lonely?”

It was a good idea. I debated the merits of leaving her at home to work it out or taking her in to work with me. Our office shared a building with a doggy day-care facility, so my first experiment involved a trial day there. I reasoned she would enjoy being with a group more than she would sitting by herself, surrounded by equally anxious dogs and cats in cages. The day care promised to put her in a room with the other big dogs and give her lots of love.

I walked over at lunch and peered in the window to see how she was doing. I surveyed the room, where bouncing Weimaraners tugged on chew toys and Golden Retrievers trotted back and forth with tennis balls. Wagging tails, relaxed eyes. After scanning for a minute, I picked out a black bucket in the corner I had assumed was a trash can. It was Kekoa, hunched down motionlessly, staring mournfully at the door. The attendant walked over and held out a ball, which she ignored. Maybe she’s just tired from all the fun she had this morning, I reasoned.

When I picked her up after work, the daily report card indicated that Kekoa had spent the entire eight-hour period in that exact position. “She seemed a little sad,” the note said in looping cursive, “but we loved having her. Maybe she’ll get used to us in time.”

The following day I decided to try bringing her directly into work instead. She immediately wedged herself under the stool by my feet, a space about an inch too short for her girth.

Good, I thought. In the time it takes her to wiggle out I can run into an exam room before she follows me.

Susan handed me the file for Room 1. I looked at the presenting complaint. “Dog exploded in living room but is much better now.”

“I hope this is referring to diarrhea, because if not we’ve just witnessed a miracle.”

“No need. It’s diarrhea.”

I popped up and ran into Room 1 to investigate the gut grenade incident before Kekoa realized I was taking off.

About two minutes into the appointment, I heard a small whine from the back hallway. Ooooooo—ooooooo.

It was soft, Kekoa whispering a song of abandonment to the empty corridor. The pet owners didn’t hear it, at first. The whimpers were drowned out by the gurgling in Tank’s belly.

“Then we gave him a bratwurst yesterday and—did I hear a baby or something?”

“Oh, you know the vet clinic,” I said. “There’s always someone making noise.”

“So anyway, I told Marie to leave the spicy mustard off but— is that dog OK?”

AoooOOoOOOOOOOOoooOOOOOOO. Now Kekoa was getting angry. I heard her claws scratching at the door.

“She’s fine,” I said. “Excuse me a moment.”

I poked my head out the door. “Manny?”

“Got it,” he said, jogging around the corner with a nylon leash in his hand. “Come on, Koa.”

“I’m so sorry,” I said, returning to Tank. I prodded his generous belly to see if he was in pain and if anything seemed swollen or out of place. “When was the last time he had diarrhea?”

“Last night,” the owner said. “But it was this weird green color and—”

He paused, furrowing his eyebrow as he looked at the back door.

A small yellow puddle of pee was seeping under the door, widening into a lake as it pooled toward my shoes.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, pulling out paper towels and wadding them under the door with my foot. I heard footsteps, and Manny muttering to Kekoa. “That’s my dog, and she is really upset I’m in here with you and not out there with her.”

Tank’s owner laughed. “Tank’s the same way,” he said.

“He ate a couch last year when we left him alone during the Fourth of July.”

“A couch?” I asked.

“A couch,” he affirmed, pulling out his cell phone for the photographic proof. He wasn’t kidding.

Excerpted from the book ALL DOGS GO TO KEVIN by Jessica Vogelsang. © 2015 by Jessica Vogelsang, DVM. Reprinted by permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

Image: Jaromir Chalabala / Shutterstock